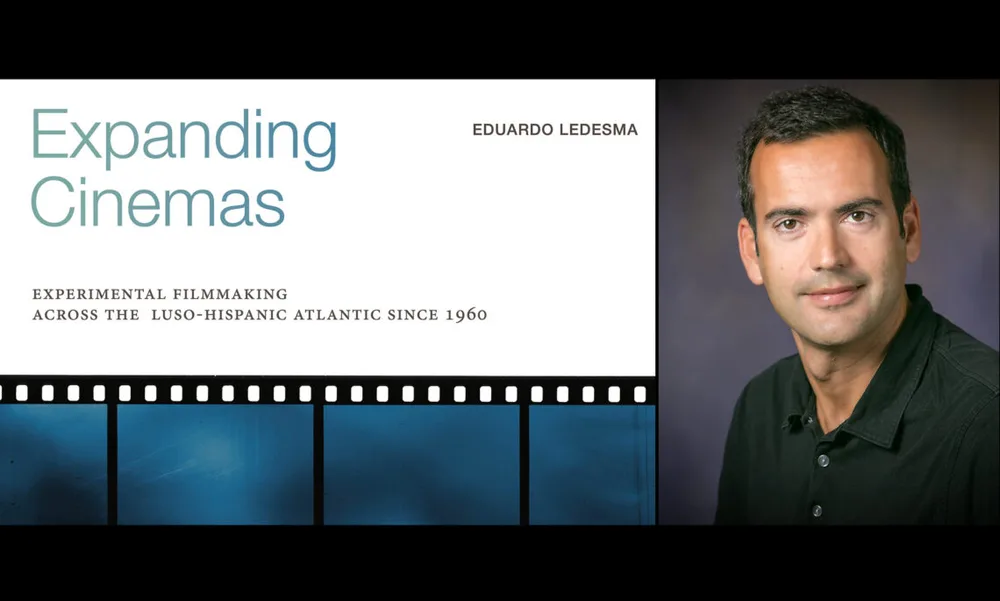

Experimental and amateur filmmakers are expanding cinema by using new technologies, such as cell phones and virtual reality, and through increasing globalization of the distribution of their work. Eduardo Ledesma, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Spanish professor, examined how experimental filmmakers in Latin America and Spain use alternative film formats in his new book “Expanding Cinemas.”

The book, which covers the 1960s to the present, studies experimental and noncommercial filmmaking, including militant cinema, documentaries, amateur films, home movies, cell phone videos, virtual and augmented reality films, artificial intelligence-generated films and audiovisual installations. The experimentation in the films includes editing, cinematography, subject matter, technologies and narrative techniques.

“A majority of the cases I study reflect the myriad ways in which film can be used as a weapon for political, social or artistic dissent against established power, whether through its form and content or how it circulates and is viewed. There are contextual, geopolitical and historical reasons for these oppositional practices,” Ledesma wrote.

Filmmakers are attracted to alternative formats for a variety of reasons, he said.

In the 1960s, militant filmmakers in countries governed by military regimes were creating clandestine anticapitalist and anticolonial work. They were looking for ways to be quick and mobile in their filmmaking, and they used handheld cameras such as the Super 8 that were cheap and easy to use and transport, Ledesma said.

Both citizen journalists and amateur filmmakers are interested in using technology such as cell phones, seeking mobility and inexpensive technologies, he said.

“They are bypassing the film industry because they don’t have connections. They are trying to do it themselves, and they have this powerful tool in their pockets,” Ledesma said. “A lot of times you can edit things right on the cell phone itself. There are a lot of works that are not particularly interesting, but creating movies with cell phones and distributing them via online platforms has opened a training space for potential future filmmakers, who might not have lot of other avenues for learning the craft, to experiment.”

He looked at filmmakers during the 1990s and 2000s who were exiled or living abroad for economic reasons. They were nostalgic for the homelands they left behind and were making movies about their sense of displacement. In some cases, the films became epistolary exchanges between filmmakers who resided on opposite sides of the Atlantic, he said. They also were nostalgic for older media such as Super 8.

“Experimental filmmakers see a sense of warmth and quality to it, especially with Super 8 images, that digital doesn’t provide,” Ledesma said.

He said there is a tension between the experimental and the commercial, and between the use of older formats and the need to digitize content to upload it to online platforms such as YouTube.

“Filmmakers want as much visibility as possible, even if their work is experimental,” Ledesma said. “There’s a tension between trying to be transgressive and independent as a filmmaker and the competing desire to have the film have as many views as possible or get invited to a festival.”

Ledesma used a description of a 2017 virtual reality installation, “Flesh and Sand,” as an example of how the notion of cinema has expanded to include various technologies and other art forms. The installation transports viewers to the U.S.-Mexico border through virtual reality. Participants wait in a cold “holding cell,” surrounded by a display of items such as shoes left behind in the desert by migrants. Then they enter and remove their shoes to feel sand under their feet. The virtual reality experience portrays a migrant’s journey crossing the border and then confronting the border patrol. After the virtual reality portion, viewers see videos of migrants telling their stories.

Ledesma said the intent of the installation is to elicit empathy for migrants, but he raised questions about the obstacles created by the technology: Admission is pricey, and the setup is elaborate so it can’t be shown in lots of places and may have a limited reach. The installation also may appeal most to viewers already sympathetic to its message, he said.

Experimental filmmakers in Latin America and Spain have provided a particular viewpoint on issues such as colonialism, migration, diaspora and hybrid identities, Ledesma wrote in his book. Such concerns are both highly localized and regionally relevant, he said.

The nationality of such films has become diffused with filmmakers uploading their work to the same platforms, tailoring it to have a universal appeal for international film festivals and often making films in English, Ledesma said. There are films that are anchored in local culture and language, but many no longer have a connection to a particular country and are products of international collaborations. Artists and audiences have moved away from national affiliation to associations along ethnic, racial or gender identifications or interest in particular genres, he said.

“People are going to find whatever they are interested in online, and viewing of individual videos is based on very particular tastes and interests,” Ledesma said.

At the end of his book, Ledesma looks at the emerging technologies of 360-degree cinema, computer-generated imagery, TikTok and artificial intelligence-generated films. He said the new formats are moving toward interactive and immersive experiences and the gamification of cinema.

“What is apparent is that spectators seek a greater degree of agency and participation in their access to contemporary audiovisual technology, beyond the role of mere consumers or passive viewership,” he wrote.

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on the Illinois News Bureau website.