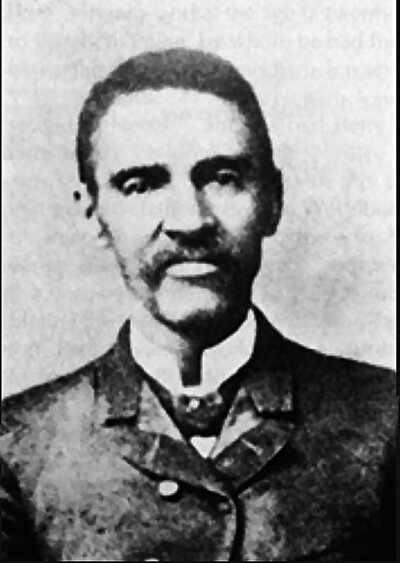

John J. Bird was one of the most prominent and influential Black men in the state of Illinois in the latter part of the 19th century, and he was the first Black board member for an essentially all-white university in Illinois – and likely in the U.S. – when he was appointed in 1873 to the board of the Illinois Industrial University, which would later become the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

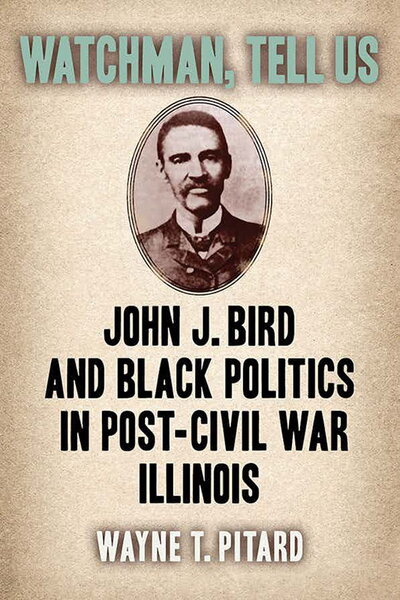

Yet he has been almost completely forgotten in the last 100 years, said Wayne Pitard, an Illinois emeritus professor of religion and former director of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures. Pitard wrote a book about Bird, titled “Watchman, Tell Us: John J. Bird and Black Politics in Post-Civil War Illinois,” that he hopes will bring new recognition to Bird’s accomplishments.

“He was part of the first generation of Black leaders (also mostly forgotten) who struggled to negotiate what was perhaps the most astonishing cultural transformation in the history of the United States, the transition of some four million people from the condition of enslavement to the status of citizen,” Pitard wrote in the book’s introduction.

Pitard learned about Bird when he was doing research for an exhibit at Spurlock for the U. of I.’s Sesquicentennial celebration, but he could find little information about him beyond his appointment to the U. of I. board.

“I thought maybe he didn’t do anything of interest. Then I looked at the Cairo (Illinois) newspaper and he pops up all the time,” Pitard said. “He’s doing all these things that are breaking racial barriers. It’s really quite astounding what he accomplished, and he did it at such a young age.”

Pitard searched the Cairo Bulletin and a predecessor newspaper, the Cairo Daily Democrat, for stories mentioning Bird. Fortunately for his research purposes, John Oberly, the editor of both papers, began to follow Bird’s career and write about him after he was appointed to the U. of I. board. Oberly was a viciously racist Democrat, but he came to admire Bird, Pitard said.

“The reason I could write this book in large part was because Oberly found Bird a fascinating subject and exempted him from his vicious attacks on Republicans. He finds him an extraordinary person and writes about him in the newspaper over and over again,” he said.

Bird’s family was part of the free Black middle class, educated and entering professional fields. His parents valued social and political activism. When Bird went to Cairo as a young man, 30% of the population was Black, the second largest Black population in the state after Chicago. Bird became a leader of the Black Republican organization in Cairo. In combination with white Republicans, they brought the Republican Party to parity with Democrats there, Pitard said.

“That meant, in the middle of the most anti-Black, Southern Democratic part of the state, there was this island at Cairo,” he said. “It changed the quality of life. For quite a while, Cairo was perhaps the best place to be Black in Illinois in terms of the kinds of things it had — an excellent public, segregated Black school run by a Black Oberlin graduate with all Black certified teachers, public buildings that were integrated and open to Black organizations, and mostly integrated hotels. It’s this remarkable island of progress, and Bird was at the forefront of all that.”

Bird was well-educated, an excellent orator and organizer, and a champion of education for Black children and higher education for Black students, Pitard said. He became the primary advocate for the Black community in Cairo and the leading Black Republican in southern Illinois. Bird helped establish a Black public school, get numerous Black elected officials in city and county government, and helped integrate most of the public businesses.

Bird also was a leader of Black state conventions that established priorities for issues important to the Black community. He pushed for laws to enforce the right to vote, forbid discrimination in public places and allow Blacks to testify in court and serve on juries, Pitard wrote.

In addition to being appointed as a university trustee, Bird was the first Black elected judge and the first Black state appointee in Illinois. He was elected as police magistrate in Cairo in 1873 and reelected in 1877 — something that would have required a substantial amount of support from white voters, Pitard said. He also was reappointed to the Illinois Board of Trustees in 1879 and elected as a justice of the peace in 1881.

Pitard said it is significant that Governor John Beveridge had the opportunity to annul his controversial 1873 decision to appoint Bird to the board shortly after he made it, when the legislature reduced the size of the board from 34 to nine seats, divided by region. Beveridge had several white candidates to choose from, and he chose to include Bird among the three trustees from southern Illinois.

Bird was widely admired for his integrity, Pitard said, but he also faced horrific racist backlash from white supremacists. And he had disagreements that damaged his standing in his own party. Bird was critical of the Republican Party for its declining support of issues of concern to Black voters. He protested the refusal of the Cairo Postmaster to hire Black employees and took the issue to the highest levels in Washington, D.C. Most damaging to his future in the party, he led a group of Black leaders in supporting a Democratic nominee, the newspaper editor Oberly, for Illinois secretary of state.

Bird’s influence had changed Oberly’s mind about Black education, and Oberly was one of very few Democrats to support a controversial 1874 bill that made it illegal to intimidate Black schoolchildren. The decision derailed Oberly’s chance to become his party’s nominee for Congress, but it won him Bird’s support when Oberly later reentered politics and ran for secretary of state, Pitard said.

Bird moved from Cairo to Springfield in 1887 and became the editor of the State Capital newspaper, which he turned into one of the most influential Black newspapers in the Midwest, Pitard said.

“He deserves to be remembered for the contributions he made,” Pitard said. “In terms of Illinois history, it’s important to know the story of African American communities beyond Chicago, and that has rarely been done in research on the African American story in Illinois.”

Editor's note: This story first appeared on the Illinois News Bureau website.