The women began to gather in the large living room, flanked on one side by a fireplace, on the other by a grand piano. As they got settled, one could hear the murmuring of soft voices and the whispers of full skirts shifting. Some students sat on the carpeted floor, others on the sofas and chairs scattered across the room.

Tonight, the women had not assembled for a traditional sorority meeting. Instead, they were here to decide the fate of two of their sisters who were discovered to have had sex with their boyfriends. The vote would be whether to banish them from the house.

Adult representatives from the sorority’s national chapter were there, too, likely making sure this chapter meeting ended the “correct” way. It was the early 1950s, and the country was navigating the beginning of the Cold War and mired in McCarthyism. Popular culture held narrowly defined gender norms tightly in its fist. Paired with a deep-rooted fear of being publicly shamed, whether for political leanings or any deviance from the norm, the atmosphere was ripe for persecution.

Sophomore Ann Thayer (BA, ’54, French) felt uncomfortable standing in judgement of her Kappa sisters. While only two women were being called out publicly, they were accused of desires and actions shared by many girls in the room. How many had yielded to the wishes of the young man they loved or were planning to marry?

Ann looked around the room at the other Kappas, beauties who were admired all over campus—by both men and women alike. Ann had seen how women looked at her sisters with longing and admiration and, in fact, saw something of herself in them.

If consorting with men were enough to be expelled from the house, what would her sisters think if they knew how Ann and others felt about women?

Ann could see the two women accused of improper behavior were crestfallen. One by one, each member cast her vote.

“Yes.” “Yes.” “Yes.”

Then it was Ann’s turn. With empathy in her heart and a tremble in her voice, Ann cast her vote.

“Yes.”

* * *

On campus, she was Ann Thayer from Hinsdale, a beautiful blonde who rushed Kappa Kappa Gamma and majored in French. She wore saddle shoes and performed in the spring carnival. In the evenings, she played piano and sang French songs at the little pub in the basement of the Union.

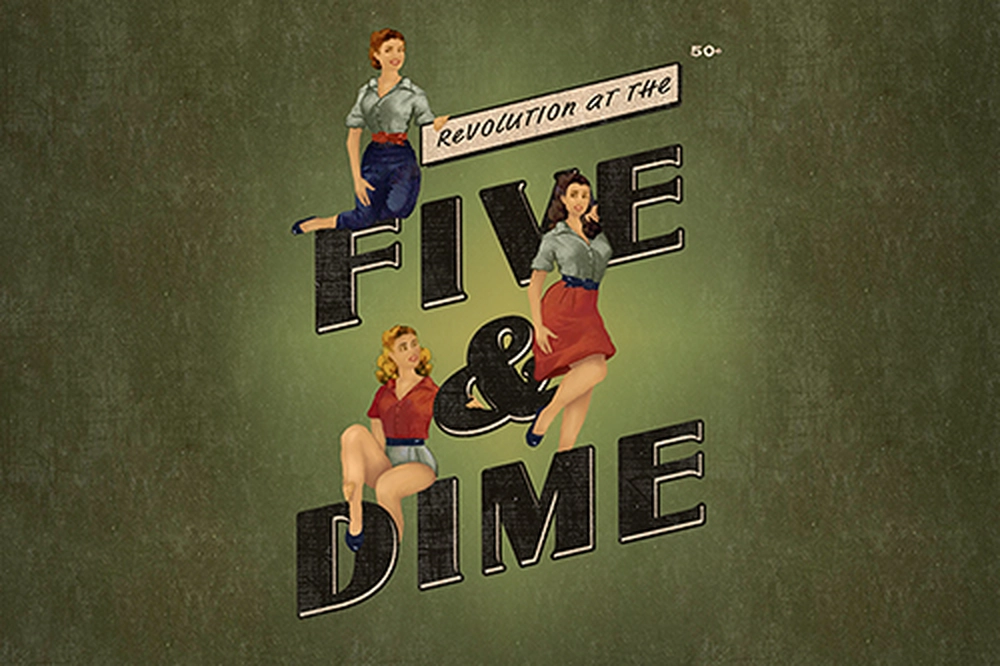

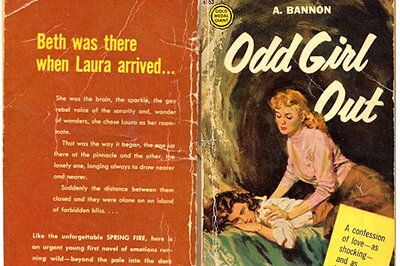

To the world, she became Ann Bannon, the name under which she published six lesbian pulp-fiction novels. Over sixty years later, these books remain fundamental to the LGBTQIA+ canon. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, her novels could be found across the country, tucked in the twisting metal racks at dime stores and adorned with illustrations of sultry women and colorful, expressive fonts. The books were shelved with Westerns and (straight) romances and detective novels, and in that way, they blended in.

But in truth, Ann’s novels, along with ones by her contemporaries, did anything but blend in. They were quietly revolutionary and became lifelines for people who felt ashamed, alone, or confused. They helped women who felt invisible be seen and gave words to describe desires in ways that had rarely appeared in the mainstream, let alone readily available for a quarter at the newsstand. It isn’t hyperbole to say that these books did more than entertain readers or create community. These books saved lives.

So, how did young Ann Thayer become iconic Ann Bannon, widely regarded as the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction?

In between her time growing up in the shadow of her prominent (and proper) Victorian grandparents and her days as a young housewife in suburban Philadelphia, Ann spent four pivotal years at Illinois.

Her experiences on campus, including the expulsion of her sorority sisters and the clandestine crushes girls had on her roommate, would find their way into the pages of her books, most directly in her first novel published in 1957, “Odd Girl Out."

Life Lessons

Ann described herself as a bookish, shy child who wore large “bottle-bottom glasses” and spent hours flipping through her mother’s beautiful books. When she was only three and four, Ann’s mother helped her memorize her favorite romantic poets, like Shelley and Wordsworth. She balanced her bookish side with a love of sports; she played tennis and swam, biked, and roller-skated.

Her grandparents were prominent figures in Chicago and suburban Hinsdale and were friendly with some of the area’s notable families. Their four-story home included a bowling alley, a top-floor ballroom, and acres of beautifully kept grounds with an apple orchard, children’s playhouse, and swings.

“Today, it sounds to me like a fairy tale,” she said. “I used to laugh about this, but I think it’s true. I could have tea with the Queen without making a fool of myself. That was my darling grandparents trying to pass along the type of life they had lived.”

Ann’s mother, Jane, while enjoying the benefits of the family’s status, didn’t always follow a straight-and-narrow path. While at the all-girls Smith College in Massachusetts, she was “campused,” meaning she couldn’t leave her dorm for a period of time. She snuck out anyway and went to the Yale prom, thinking she had gotten away with it.

“The next morning,” Ann explained, “the newspaper ran a picture of the prom queen, and it was my mother! Her career at Smith came to a crashing end.”

Not long after that, now at Rockford College, Ann’s mom fell in love with a boy she quickly and secretly married. It was only five months later, when the family came to see her in a school play, that suspicions were raised about Jane’s activities. Noticing her sibling’s growing midsection from the audience, Jane’s sister leaned over to their mother and whispered, “Mom, Jane’s pregnant!”

“My mother was an extraordinary young beauty, and I was a sort of grim surprise,” Ann said, laughing. “At that time, it was not thought appropriate to enlighten girls about sex. My grandparents immediately put her in a private suite in the hospital. She sat in that room for the next four months, and she smoked cigarettes and read Dickens.”

Ann admits that the influence of her Victorian grandparents, paired with the oppressive expectations of women in the mid-twentieth century, amounted to her coming to campus rather naïve. She was excited about the new experiences Illinois offered her, but she also clearly understood the rules that were carved out by society, and that until this point, she perhaps hadn’t questioned them.

Starting a new chapter

On campus, Ann threw herself into activities and social clubs. In some ways, she felt living in the Kappa Kappa Gamma house was like being transported back to her childhood and the comforts of her grandparents’ home.

She thrived in the all-female environment, making close friends and enjoying herself immensely. And beyond the student theater productions and the sorority socials, there lurked another kind of freedom, another door that began to open for Ann.

Every new initiate was paired with an upper-class member, which is how Ann became close with her roommate Mary. “There was another sorority next to ours, and one of the girls came over all the time. She was completely besotted by Mary and would look at her worshipfully. Mary was awfully embarrassed, but I could see why this happened. I had never been introduced to anything like that, but I was intrigued. Still, I was very cautious and didn’t want to get in trouble.”

Ann reckoned with these feelings but didn’t act on them while on campus.

“At that time, homosexuality was considered a disease. People were diligently trying to ‘cure’ it. And the thinking was that it was so appealing and so seductive, that once you were exposed to it, you’d never recover,” she said.

“The people who felt these stirrings heard this loud and clear. How could we live a life that allowed us to express ourselves?”

On campus, books about queer attraction were kept behind lock and key, in what some people colloquially called “the cage” and what the Main Library first called the “vault.” (Ultimately it was named the “Bookstacks Delayed Access Area.”) Ostensibly created to protect fragile or rare books and manuscripts, the cage also included titles that were deemed inappropriate.

In Ann’s day, she would have to approach a professor and request written access to the space, something she found incredibly difficult to do.

“There were a few books filled with misinformation about what it was to be a homosexual. They were more likely to terrify you, just heart-wrenching and terrible stories,” she recalled. “Here you are, starting to acknowledge these feelings, if only to yourself, and you think, who can I turn to for information or support? Not your family. Not your pastor. Not your doctor. Not these books.”

At the time, books were some of the only places to find information, especially in a safe and private way, although so few of these were supportive or helpful. It is what makes Ann’s books, which were published between 1957 and 1962, so significant. She dared to create characters whose complicated feelings were the opposite of terrifying. They were warm, compassionate sketches of women in love.

Yet, Ann’s books would likely have shared shelf space in the cage for years until, according to an annual report, a policy change led the library to “liberate about 600 books to the open shelves.”

That was in 2002.

Writing a lifeline

One evening, while playing piano and singing in the Union basement, Ann met a very handsome older student. He had spent time overseas during WWII engaged in research for the military and was now back on campus to finish his engineering degree. He asked if he could have her number, much to the chagrin of the date he left sitting at his table.

Ann ended up marrying him, and while the marriage was difficult, they stayed together for nearly 30 years before divorcing. Because he didn’t want Ann to have a job as a newlywed, she found herself sitting before a typewriter at the dining-room table while her husband was at work. Her fingers danced across the keys, committing to paper a world where it was okay to express love and desire for another woman, and in so doing, she created a safe fantasy life for her readers—and herself.

Her first book, “Odd Girl Out,” is set in a thinly veiled version of Champaign-Urbana, with characters inspired by her sorority sisters, including Mary, who meet on Wright Street and go to class at Lincoln Hall.

“I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of twenty-two to write a novel,” Ann admitted in a 2002 introduction to “Odd Girl Out.” “It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience.”

Eager to get the book published, Ann approached another writer of lesbian pulp fiction, Marijane Meaker (writing as Vin Packer), who offered to share Ann’s manuscript with her publisher.

The instant success of “Odd Girl Out” led to four additional novels, collectively known as “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.” While “Odd Girl Out” was a hot title for publisher Gold Medal Books, the reception from her family was a little cooler.

“It’s hard, really, to keep going in spite of the shocked expression on the face of your beloved family,” she said. “The last thing you would want to do is cause them public humiliation, and I did. They certainly didn’t throw me out of the family, but they were taken aback, and I shrank from that a bit.”

Ann’s husband didn’t approve of her books either, reading only a few paragraphs of “Odd Girl Out” before he stopped reading her books altogether. “He realized there was a whole part of me he couldn’t control. Nevertheless, when my checks came in, he always went to the bank with a smile.”

Ann’s books were published in a time when queer pulp fiction was considered pornographic. Because the books would ship to retailers through the U.S. Postal Service, Congress was able to censor the material. This meant that for many years, these books were not allowed to have happy endings; the characters would have to suffer for the “sin” of being gay.

Rules began to relax shortly after Ann began publishing.

“I gave at least some of the stories a happy ending, sort of. Nobody had to be shot or jump in front of a train for the sin of loving another woman,” Ann wrote in the same introduction. “Bad things did happen that reflected the arrogant ignorance of the authorities, the contempt of conventional society, and the occasional desperation of the women of the times; modern readers may feel impatient with some of this now, but it was part of life back then. But still there was humor and there was love, in at least as good measure, and I am most proud of having captured some of that temper of the times as well.”

Ann quickly found that her books struck a chord with readers, and the letters she received from fans revealed just how important these books were to so many women.

Ann remembers one girl’s letter in particular. “She was a brilliant writer and a girl of eighteen when she found “Odd Girl Out” on a drugstore shelf. She had been on her way to the bridge across the river in her town in Canada. She was so sick at heart that she was going to jump off, and as she put it, ‘I sat down and read that whole book in a gulp, and I got up from the bench in the park, and I went home for dinner instead.’ I heard an awful lot of stories like that.”

“Above and beyond being an essential source of information, these books were among the few places you could take your imagination and your heart and make up your mind to keep going,” Ann said.

To thy happy children of the future…

Ann, now 90, spent only a small percentage of her life as a pulp-fiction author. She stopped writing novels in the early 1960s, moving instead toward academic pursuits. She earned her PhD at Stanford, had a long and rewarding career as a university dean and professor, and raised two children. She holds all these identities close to her heart, noting that each is as precious to her as the others.

Along the way, Ann has been reticent to label herself. “We didn’t have the language to talk about what the kids are talking about now. Bisexual or gender fluid, that would have suited me. That’s where I should have placed myself, but it took a long time [for the culture] to develop a language with some dignity and some breadth and depth. I was in every character, even the boys. I’ve been all of them. And I love all of them. They are there for me anytime I want to go back and visit,” she said. The legacy of her books persists. She managed to freeze a moment in time that has survived on well-worn pages and between tattered covers, regardless of the ways in which our cultural pendulum has swung one way or the other.

“The books developed a life of their own. They went out in the world and gave comfort and insight and knowledge to young women who were so isolated and frightened and insecure,” Ann said. “That was a gift. At the time, I was ignorant that I was giving it. I didn’t realize how much of an influence they would have.”

She is still a star at paperback conventions across the country, first editions of “Odd Girl Out” can sell for hundreds of dollars, and her books are taught in college courses—including at Illinois.

Associate professor Siobhan Somerville teaches Ann’s books in her class and finds that the novels are important to LGBTQIA+ studies.

“Not only because they are written in an entertaining way (full of steamy scenes of desire between women, for instance), but also because they could be considered an archive of the feelings of white women who pursued lesbian relationships during the Cold War period,” Somerville said. “At a time when lesbian relationships were sensationalized or stigmatized in popular culture, law, and medicine, Bannon’s novels register the range of complicated feelings—positive and negative—that swirled within those women.”

Ann returned to campus to give a guest lecture in 2004, and while here she made the requisite stop at the Alma Mater. She has never forgotten Alma’s motto, and she gets choked up when she recites it to me by heart. “I get emotional. I imagined myself as one of the children of the past greeting the children of the future. It’s touching to me.”

I tell her that often when I interview alumni about their time at Illinois, their emotions and memories are surprisingly vivid. Sometimes it can be easier to remember a spring afternoon on the Main Quad with Altgeld’s bells chiming the hour than what we had for lunch yesterday.

Ann explained it this way: “In other times of your life, you remember what you did. But when you were in college and learning to be an adult, you remember how you felt. You travel back there in your heart, not just your mind.”

Kim Schmidt

Editor's note: This story first appeared in Storied.