Faculty from Second Language Acquisition and Teacher Education (SLATE), the Department of Linguistics, and the Program in Translation and Interpreting Studies are collaborating with the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) to develop an online training program for interpreters for Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings in Illinois schools.

The five-year, $5 million project follows a recently enacted law that requires qualified interpreters to be present when teachers and parents meet to discuss IEPs for students with special educational needs.

“With this law, K-12 kids who have IEPs and who come from a home where English is not the main language spoken will be much better served,” said Joyce Tolliver, director of the Program in Translation and Interpreting Studies.

The online program being developed at the University of Illinois will establish language proficiency, instruct future interpreters in relevant special education vocabulary and concepts, and train them in the ethics, protocols, and skills required for interpreting and translation.

“It’s an important step toward remedying a real problem: the common misperception that anyone who speaks two languages—or even, anyone who speaks one language and has some degree of competence in a second—can work as an interpreter,” said Tolliver. “Interpreting requires a combination of high-level cultural, linguistic, and analytical skills, as well as background knowledge of the topic being discussed and a firm grasp of professional ethical standards.”

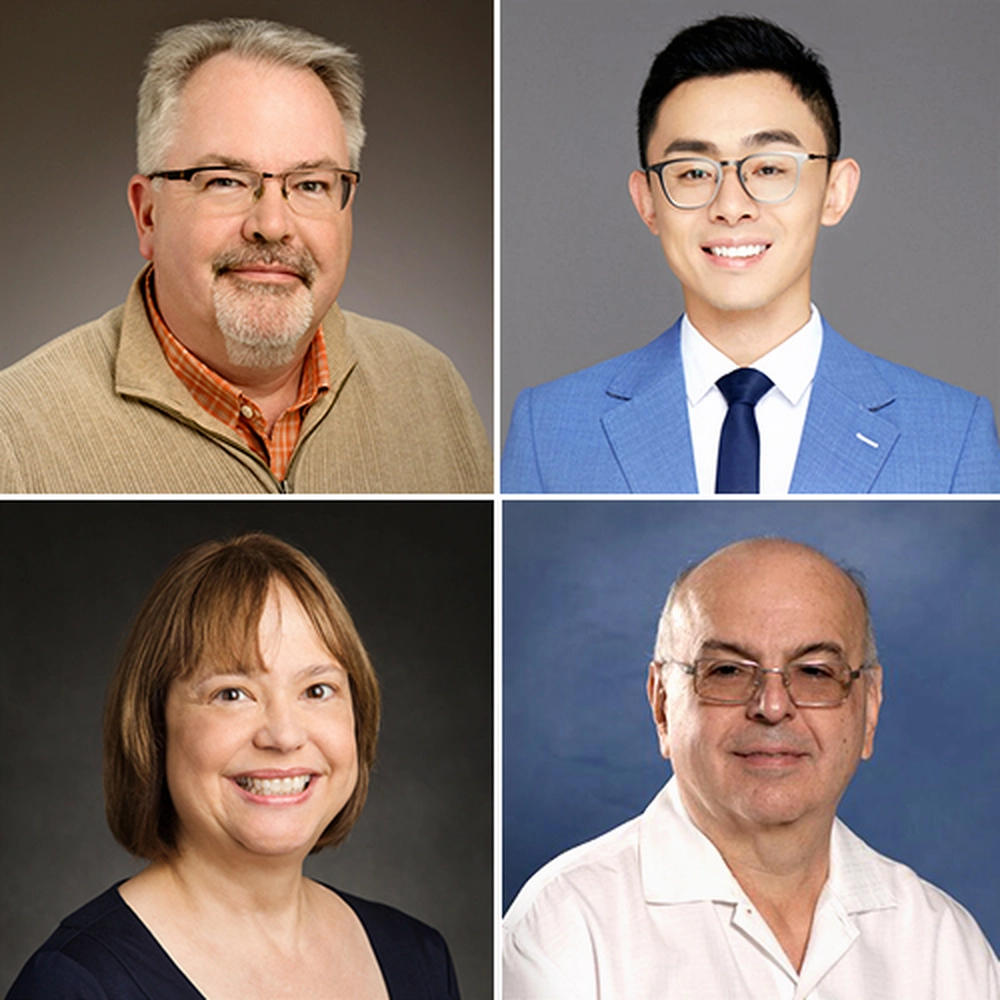

Tolliver is one of five University of Illinois professors who are working to make sure interpreters have the training they need to meet these qualifications. She’s joined by Kiel Christianson, director of SLATE and chair of the Department of Educational Psychology; Xun Yan, professor of linguistics; Reynaldo Pagura, professor of translation and interpreting studies; and Hedda Meadan-Kaplansky, professor of special education.

Each team member has an important role to play in the development of this online training program. Tolliver will be working closely with Pagura on the design and implementation of the interpreting education portion.

Meanwhile, Yan is leading the development of proficiency tests in multiple languages that can be used to certify qualified interpreters and diagnose the strengths and weaknesses of their language skills for training purposes. He’s currently working with Christianson and five graduate research assistants in the Departments of Linguistics, Spanish & Portuguese, and East Asian Languages & Cultures to create prototypes for the proficiency tests.

“[This is] a textbook example of how scholarly expertise and the collaborative atmosphere afforded by a world-class university can benefit society as a whole,” said Christianson.

The team is currently building a beta-version of the online training program. They hope to begin testing it with a small number of trainees within the next several months.

The project is beginning with the five most widely spoken non-English languages in Illinois: Spanish, Polish, Arabic, Urdu, and Russian.

At present, there are about 166 total non-English languages spoken by students in Illinois schools. The ultimate goal is to develop this resource for all of them.

“So much remains to be done to ensure the equity and equality in K-12 education,” said Yan. “With more qualified interpreters available within the state, we hope to reduce the gap in educational resources and opportunities among students [who come from families where English is not the home language.]”

The team hopes this project will also serve as an example for other states. In the meantime, they’re asking anyone who speaks one of these languages and would like to train as an IEP interpreter to contact them.

Dania De La Hoya Rojas